Overview

This project was built using a combination of ROS, Gazebo, and Python. We primarily built our project around the

neato simulator

to use for testing, but with a few adjustments to ROS parameters, our project should be easily portable to any robotics platform.

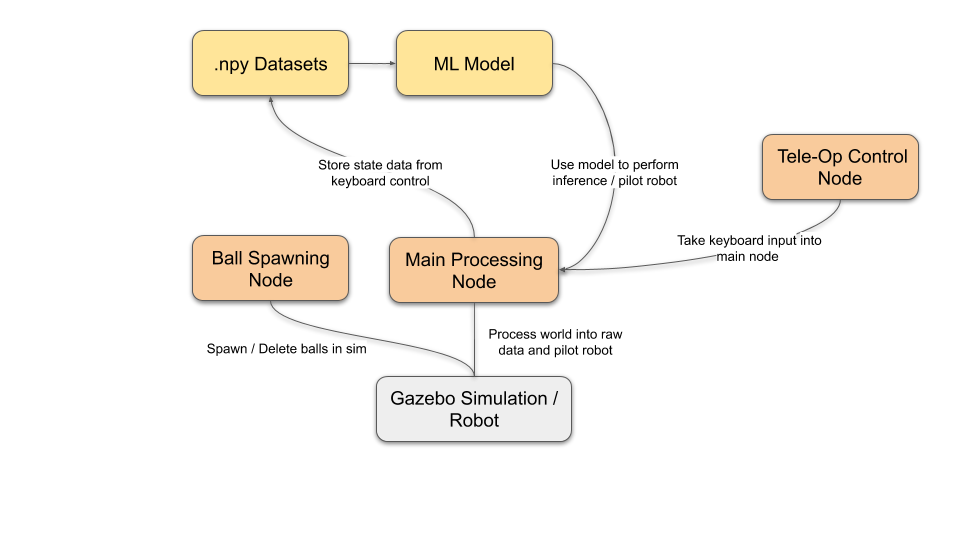

Our system is broken into several categories, that each are made up of smaller parts:

- ML Network

- Training the network

- Using the network to generate motor commands

- Gazebo and Robot Simulation

- Recording data of the world

- Generating model inputs

- Generating model training data

- Creating and managing the dodgeball simulation

These systems are broken down into finer detail in the sections below.

System Architecture

Ball Spawner

This code lives in the script ball_spawner.py and is controlled via ros parameters to ensure that the environement is consistent across all parts of the system (think spawning the same number of balls as recording and generating model inputs for)

If this entire system has a heart – the ball spawner is it. The ball spawner is in charge of all things related to managing balls in the system. This boils down to several things:

- Spawning new balls in the appropriate spots

- Deleting balls that are no longer a “threat”

For our purposes, we are interested in balls spawning in several different scenarios. The reason for building a robust ball spawner is so the difficulty of our problem can easily be scaled. For example: we were interested in making a system that dodged single balls at a time as well as a system that dodged multiple.

To implement this we use a singular ROS node that uses Gazebo Services. Gazebo Services allows for easy creation and deletion of gazebo models (aka dodgeballs).

Our modeling success depends directly on the quality of our training data. This means that the ball spawner needs to produce a wide variety of output. The method we used to do this is to spawn balls randomly within a certain range of the robot, and with a random velocity that was constrained by other parameters. This allows for the ball spawner to spawn, completely random balls, balls that only go straight, and one’s that target the robot.

Ball cleanup is done by removing any balls that have moved past the neato

Gazebo Processor

The script process_gazebo.py starts up the main processing node which handles the interface between our machine learning models and gazebo. Here’s a list of the ROS parameters that this node listens to:

dodgeball_prefix: Name of the dodgeballs - used to extract model states from gazeborobot_name: Name of the robot model - used to extract model state from gazebonum_dodgeballs: Number of closest dodgeballs to keep track ofrun_model: Set to 0 for data recording mode, 1 for model testing modeuse_origin: Sets whether or not the robot’s position in global coordinates should be used in the modelsave_filename: Dataset save file location (will save to a .npy file)model_path: File location of the machine-learning based controller - assumes LSTM models start with the prefixLSTMand standard models with the prefixstandardrate: Node update rate in Hz

This node has two primary modes - a “data collection” mode, and a “run model” mode. When the run_model ROS parameter is set to 0, the node will run in its data collection mode. The function that does most of the heavy lifting here is the recordDataPoint function, which records each of the balls’ position and velocity relative to the robot as well as the current operator command. It records this data for the first n balls, where n is equal to the number of dodgeballs as specified by the ROS parameter num_dodgeballs. If use_origin is set to true, it will also record the robot’s position in global coordinates as part of the training dataset. All of this data then gets saved to a dataset as a .npy file, and is used later for training our machine learning models.

When this node is in “run model” mode, it still uses much of the same initial data processing code but doesn’t actually record any of the data it sees. In this mode, the node will once again use the recordDataPoint function, but instead of taking the output data and writing it to a file for later use, it passes the data point to the model specified in the parameter model_path. Since the LSTM and standard models are saved in two different ways (caused by the two different libraries used for their respective implementations), they look at the prefix of the model name to determine how to correctly load the data. From here, it will publish the output of the model to the ROS topic /cmd_vel, and its efficacy can be seen in the Gazebo window for model testing.

Teleop-Control

We also implemented two types of teleoperated control for recording our datasets: a keyboard-based controller, and a joystick-based controller. We wanted to have a keyboard-based controller since not all of our team members had a joystick on hand that they could use, and it’s oftentimes more straightforward to test with a controller during earlier stages of debugging. However, we also wanted to have a joystick-based controller so that we could record datasets with continuous inputs, which we hoped would smoothen out the data and make it easier for the model to learn what we wanted it to.

Our keyboard-based controller was essentially a modified version of the

ROS teleop_twist_keyboard

node - we took the node available at that repo and added “start” and “stop” keybindings to it. When the ‘s’ key is pressed, the node publishes a message to the topic spawn_cmd, which tells the ball spawner node to start creating balls in gazebo. When the spacebar is pressed, it publishes a message to both the topic spawn_cmd and save_cmd, which tells the ball spawner node to remove all of the balls and tells the gazebo processing node to save the accumulated data to a .npy file.

Our joystick-based controller node was a modified version of Amy’s teleop code from her warmup project, with minor edits to also add “start” and “stop” keybindings to it. Instead of the ‘s’ and spacebar keys, however, “start” and “stop” were bound to the ‘A’ and ‘B’ buttons, respectively. This was tested on an Xbox 360 controller, which was used to record most of our continuous datasets. This teleop code should work with other controllers as well, but the exact buttons may vary based on the type of controller.

ML Networks

Please see our other documentation about the ML networks created: